Indonesias Ratification of Apostille Convention Should Boost Ease of Doing Business

After almost sixty years since its adoption, Indonesia finally ratified the Convention to Abolish the Requirement for Legalisation of Foreign Public Documents (the “Convention”) via Presidential Regulation No. 2 of 2021 (“PR 2/2021”), on 4 January 2021. The ratification sends a positive signal to Indonesia’s legal community in particular amid the Covid-19 pandemic; and to the business sector in general, because it simplifies the legalization of foreign documents, which has always been time-consuming – even under normal circumstances, let alone a pandemic.

A. Legalisation by Apostille

Article 2 of the Convention describes legalization as “the formality by which the diplomatic or consular agents of the country in which the document has to be produced certify the authenticity of the signature, the capacity in which the person signing the document has acted and, where appropriate, the identity of the seal or stamp that it bears.”

Under the Convention, legalization is a State procedure in which a document is produced to “authenticate” a signature to confirm that it was signed by its actual bearer within their authorized capacity. Each State may have its own legalization procedure. Generally, the procedure may involve a notary, a court or the justice ministry, the ministry of foreign affairs, and the representative office (embassy or consulate) of the destination country.

Indonesian law has a similar definition for legalization. According to Ministry of Foreign Affairs Regulation No. 13 of 2019 on Document Legalisation Procedures at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the “MoFA Regulation”), legalization focuses on the authentication of a document and the signature and/or stamps, not the substantive content of a document.

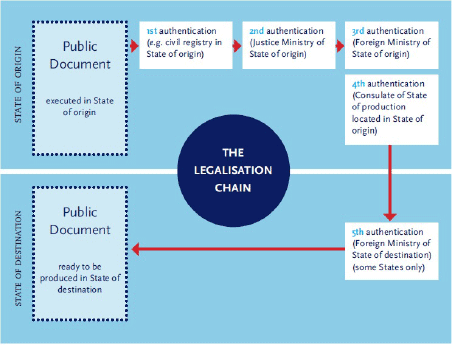

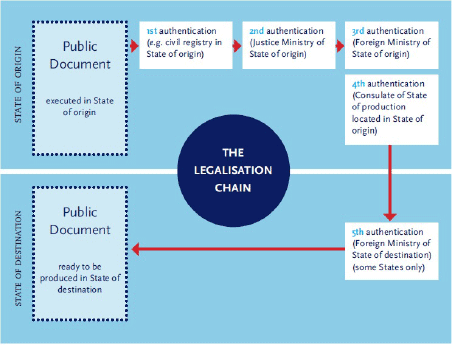

Prior to the ratification of the Convention, legalization generally adopted the following procedure:

(taken from the Apostille Convention Handbook, p.3)

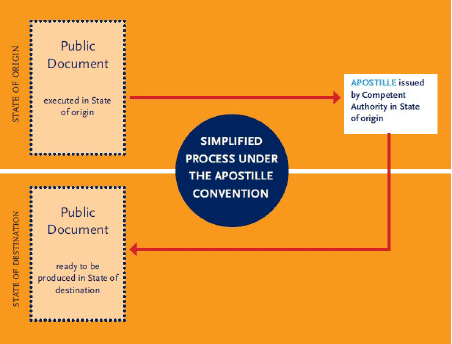

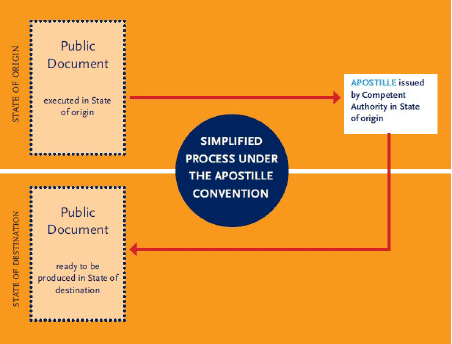

After ratification of the Convention, authentication will have the same effect but be considerably more streamlined:

(taken from the Apostille Convention Handbook, p.5)

This is particularly beneficial for transactions and actions where speedy authentication is of the essence.

B. Applicability and Exclusions

1. What constitutes a public document

An apostille is applicable to public documents, which under Article 1 of the Convention are:

- documents emanating from an authority or official connected with the courts or tribunals of the State, including those emanating from a public prosecutor, a court clerk or a process-server ("huissier de justice");

- administrative documents;

- notarial acts;

- official certificates appended to documents signed by persons in their private capacity, such as an official certificate that records the registration of a document or the fact that it was in existence on a certain date, and the official and notarial authentication of the signatures it contains.

Point (d) above expands applicability to certain private documents: when the signature in a private document is authenticated by a notary official, then the notarial authentication in that private documents is considered to be an official certificate that constitutes a “public document”.

Within this context, the treatment of a document may also depend on how it is defined in its original jurisdiction, which usually determines whether a document falls into the category of a document that must be apostilled or legalized.

The method of legalization is further dependent on the requirements applicable in each state. The MoFA Regulation requires any Indonesian document to be used abroad, or a foreign document for use in Indonesia, to be legalized by the authorized institution. Therefore, once the Apostille Convention has become effective for Indonesia it would be logical that the apostille will in time replace legalization under the MoFA Regulation for the documents originating from a member state of the Convention.

2. Exclusions

The Convention does not apply to documents executed by diplomatic or consular agents, or administrative documents dealing directly with commercial or customs operations.

PR 2/2021 also stipulates that documents issued by a prosecutor’s office in Indonesia must still follow the legalization process applicable in Indonesia.

Exemption from the requirement for legalization applies only to states that are parties to the Convention. Conversely, the legalization procedure continues to apply to Indonesian documents for use in states not a party to the Convention, and vice-versa.

C. Implementation

Although already promulgated, PR 2/2021 is still dependent upon the issuance of an implementing regulation, particularly because the Convention requires a contracting state to appoint a Competent Authority as the agency to take responsibility for the apostille process. The implementing regulation should also address the potential ambiguity over the definition of public documents in Indonesia, as well as the extent to which an apostille is applicable, and how Indonesian parties must treat a document that has been apostilled rather than legalized.

While the Government’s attempt to simplify legalization procedures is laudable, an implementation regulation will provide essential guidance for clear and effective implementation of PR 2/2021.

By partners Mr. Sahat Siahaan (ssiahaan@abnrlaw.com) and Ms. Ulyarta Naibaho (unaibaho@abnrlaw.com) and foreign counsel Mr. Theodoor Bakker (tbakker@abnrlaw.com). Eva Fauziah (efauziah@abnrlaw.com) provided valuable assistance to the preparation of this article.

This ABNRNewsand its contents are intended solely to provide a general overview, for informational purposes, of selected recent developments in Indonesian law. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Accordingly, ABNR accepts no liability of any kind in respect of any statement, opinion, view, error, or omission that may be contained in this legal update. In all circumstances, you are strongly advised to consult a licensed Indonesian legal practitioner before taking any action that could adversely affect your rights and obligations under Indonesian law.

More Legal Updates

- 20 Feb 2026 ABNR Lawyers Present at IJM-Hosted Session on Child Protection and Electronic Evidence with Indonesian National Police

- 12 Feb 2026 A rising star shines brightest when supported by a strong foundation.

- 09 Feb 2026 ABNR Shares Insights with OJK on KUHAP 2025 and Its Potential Impact on Criminal Investigation in the Financial Services Sector

- 09 Feb 2026 ABNR Partners Engage with OJK on SOE Law Revisions and Financial Sector Oversight

- 04 Feb 2026 Corporate Actions in Indonesia Face New Scrutiny under MOL Regulation No. 49 of 2025

- 02 Feb 2026 ABNR Advises CBL Group on Strategic Acquisition of PT Tri Jaya Tangguh

NEWS DETAIL

16 Feb 2021

Indonesias Ratification of Apostille Convention Should Boost Ease of Doing Business

After almost sixty years since its adoption, Indonesia finally ratified the Convention to Abolish the Requirement for Legalisation of Foreign Public Documents (the “Convention”) via Presidential Regulation No. 2 of 2021 (“PR 2/2021”), on 4 January 2021. The ratification sends a positive signal to Indonesia’s legal community in particular amid the Covid-19 pandemic; and to the business sector in general, because it simplifies the legalization of foreign documents, which has always been time-consuming – even under normal circumstances, let alone a pandemic.

A. Legalisation by Apostille

Article 2 of the Convention describes legalization as “the formality by which the diplomatic or consular agents of the country in which the document has to be produced certify the authenticity of the signature, the capacity in which the person signing the document has acted and, where appropriate, the identity of the seal or stamp that it bears.”

Under the Convention, legalization is a State procedure in which a document is produced to “authenticate” a signature to confirm that it was signed by its actual bearer within their authorized capacity. Each State may have its own legalization procedure. Generally, the procedure may involve a notary, a court or the justice ministry, the ministry of foreign affairs, and the representative office (embassy or consulate) of the destination country.

Indonesian law has a similar definition for legalization. According to Ministry of Foreign Affairs Regulation No. 13 of 2019 on Document Legalisation Procedures at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the “MoFA Regulation”), legalization focuses on the authentication of a document and the signature and/or stamps, not the substantive content of a document.

Prior to the ratification of the Convention, legalization generally adopted the following procedure:

(taken from the Apostille Convention Handbook, p.3)

After ratification of the Convention, authentication will have the same effect but be considerably more streamlined:

(taken from the Apostille Convention Handbook, p.5)

This is particularly beneficial for transactions and actions where speedy authentication is of the essence.

B. Applicability and Exclusions

1. What constitutes a public document

An apostille is applicable to public documents, which under Article 1 of the Convention are:

- documents emanating from an authority or official connected with the courts or tribunals of the State, including those emanating from a public prosecutor, a court clerk or a process-server ("huissier de justice");

- administrative documents;

- notarial acts;

- official certificates appended to documents signed by persons in their private capacity, such as an official certificate that records the registration of a document or the fact that it was in existence on a certain date, and the official and notarial authentication of the signatures it contains.

Point (d) above expands applicability to certain private documents: when the signature in a private document is authenticated by a notary official, then the notarial authentication in that private documents is considered to be an official certificate that constitutes a “public document”.

Within this context, the treatment of a document may also depend on how it is defined in its original jurisdiction, which usually determines whether a document falls into the category of a document that must be apostilled or legalized.

The method of legalization is further dependent on the requirements applicable in each state. The MoFA Regulation requires any Indonesian document to be used abroad, or a foreign document for use in Indonesia, to be legalized by the authorized institution. Therefore, once the Apostille Convention has become effective for Indonesia it would be logical that the apostille will in time replace legalization under the MoFA Regulation for the documents originating from a member state of the Convention.

2. Exclusions

The Convention does not apply to documents executed by diplomatic or consular agents, or administrative documents dealing directly with commercial or customs operations.

PR 2/2021 also stipulates that documents issued by a prosecutor’s office in Indonesia must still follow the legalization process applicable in Indonesia.

Exemption from the requirement for legalization applies only to states that are parties to the Convention. Conversely, the legalization procedure continues to apply to Indonesian documents for use in states not a party to the Convention, and vice-versa.

C. Implementation

Although already promulgated, PR 2/2021 is still dependent upon the issuance of an implementing regulation, particularly because the Convention requires a contracting state to appoint a Competent Authority as the agency to take responsibility for the apostille process. The implementing regulation should also address the potential ambiguity over the definition of public documents in Indonesia, as well as the extent to which an apostille is applicable, and how Indonesian parties must treat a document that has been apostilled rather than legalized.

While the Government’s attempt to simplify legalization procedures is laudable, an implementation regulation will provide essential guidance for clear and effective implementation of PR 2/2021.

By partners Mr. Sahat Siahaan (ssiahaan@abnrlaw.com) and Ms. Ulyarta Naibaho (unaibaho@abnrlaw.com) and foreign counsel Mr. Theodoor Bakker (tbakker@abnrlaw.com). Eva Fauziah (efauziah@abnrlaw.com) provided valuable assistance to the preparation of this article.

This ABNRNewsand its contents are intended solely to provide a general overview, for informational purposes, of selected recent developments in Indonesian law. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Accordingly, ABNR accepts no liability of any kind in respect of any statement, opinion, view, error, or omission that may be contained in this legal update. In all circumstances, you are strongly advised to consult a licensed Indonesian legal practitioner before taking any action that could adversely affect your rights and obligations under Indonesian law.